Think Space

Through the looking Glass

Autor/izvor: DAZ / Think Space 19/09/2013

Uskoro nam predstoji početak novog ciklusa Think Space programa. Kao uvod donosimo vam neke od najzanimljivih radova s prošlogodišnjeg Think Space-a i izdanja Call for Papers / Poziva na objavu stručnih i teorijskih radova u arhitekturi. Među prvima predstavljamo rad Through the looking glass autorice Ishite Chatterjee.

U svom tekstu autorica se bavi trima subjektima; kućom Farnsworth Ludwiga Mies Van Der Rohe, kućom Glass House Philip Johnson i socijalnom mrežom Facebook. Kako privatnost u ikoničkim djelima arhitekture poput navedenim staklenim kućama funkcionira je pitanje koje zadržava svoju konceptualnu, kao i fundamentalno pragmatičnu aktualnost. U kontekstu sa socijalnim mrežama privatnost je definitivno prošla tranziciju kao socijalna kategorija. Kako neki koncepti i pojmovi kroz arhitektonsku i socijalnu prizmu današnjice interferiraju pročitajete u nastavku u tekstu Ishita Chatterjee koji donosimo u cijelosti.

Sve tekstove odabrane za objavu u prošlom Think Space ciklusu PAST FORWARD možete preuzeti ovdje u PDF-u.

Ovom prilikom pozivamo Vas na predstavljanje novog ciklusa programa Think Space u Laubu, utorak 24.rujna 2013. u 18h.

Temu ciklusa MONEY/ NOVAC i prvi natječajni zadatak Territories/ Teritoriji predstavit će gosti kustosi Ethel Baraona Pohl i César Reyes Nájera (dpr-barcelona), a u interdisciplinarnom razgovoru za okruglim stolom uz goste kustose sudjelovat će dr.sc. Mario Vrbančić (Filozofski Fakultet u Zadru), Željko Ivanković (časopis Banka) i Marko Dabrović (3LHD).

Razgovor će moderirati dr.sc.Tomislav Pletenac (Filozofski fakultet u Zagrebu).

THROUGH THE LOOKING GLASS

- Ishita Chatterjee

PREFACE

‘I would think here where everything is beautiful, and privacy is no issue, it would be a pity to erect an opaque wall between the outside and the inside. So I think we should build the house of steel and glass; in that way we’ll let the outside in. If we were building in the city or in the suburbs, on the other hand, I would make it opaque from outside and bring in the light through a garden-courtyard in the middle.’

1949, Mies Van Der Rohe to Mrs Farnsworth

‘I mean the idea of a glass house, where somebody just might be looking—naturally, you don’t want them to be looking. But what about it? That little edge of danger in being caught. Sometimes a little kid masturbates because he wants to get caught.’

1949, Philip Johnson

The Farnsworth house and the Glass house which were conceived as an extension of the plan accomplished much more than dissolving the boundary between the outside and the inside; they questioned dwelling at a fundamental level. What is a house? What can a house be?

‘Privacy no longer a social norm’

2010, January 8 San Francisco, Mark Zuckerberg during the Crunchie Awards

Facebook has transformed the way people interact with each other. The social networking website that started off trying to answer simple fundamental questions - how to connect? How to reach out? - has become a tool of change, the world over. While some nations have benefited from its ability to instigate a revolution, others, threatened by it, have banned it.

The above mentioned quotes introduce the three subjects of this essay namely – The Farnsworth house, the Glass house and Facebook. In the first scenario, the principal subject Mrs Farnsworth was subjugated by the other subject, her house – the Farnsworth house – and subdued to an object. In the second scenario, Philip Johnson, the owner, as well as the architect of the Glass house, was always in control of the house and hence didn’t play second fiddle to it. He oscillated between being the subject and the object as and when he desired. In the third scenario: within Facebook, there is an ongoing battle for control of information. Facebook maintains that it gives its users the freedom to decide whether it wants to be the subject or object but the irony here is that the even the inception of Facebook meant we[i] all became objects.

Separated by a century, diverse audience, disparate subjects, different objects, the three subjects have one thing in common; the object in all the cases is aware of being objectified. The properties of glass houses in the physical world and social networking sites in the virtual world have certain similarities as well as differences. Another thing that the three have in common is that they all pushed the envelope on privacy. The three subjects were pivotal in defining, redefining and challenging the concepts of privacy. They dissolved the boundary between the personal and the impersonal.

The concept of privacy is ever evolving. It alters with technological progress as well as changing social values and attitudes of society. The concept is also a relative one; it means different things to different people, societies, and countries, thereby making it extremely difficult to define the idea. Modernism[ii] led to structuring of society, and privacy became an important social issue. Privacy, as we know today, was born in 19th century. The modern[iii] view of privacy requires a well-defined separation between the public and the private. These issues are dealt with very differently in different countries. Each country’s history leads to a very different interpretation of this boundary. The two glass houses were built in a country (the United States of America) which was formed due to a dispute over this boundary[iv].

This essay analyses the two iconic and canonic houses, the Farnsworth house by Mies Van Der Rohe, the Glass house by Philip Johnson and compares it to Facebook. It looks at the concept of privacy in the 21st century, and whether it has evolved/changed in any way from the 20th century. The first and the second chapter give a brief background of Facebook and the two glass houses respectively. This helps in understanding the significance of glass houses during the 1950s and its implications today, in the age of Social Media. The subsequent chapters analyse the interface/window of the three subjects and discusses the issue of privacy through comparative analysis of the glass houses and Facebook.

1.0. FACEBOOK

Facebook started off as a small, personal college community back in 2006 and transformed into a larger, impersonal social platform. It allows users to voluntarily divulge their personal information like location and activities to any of their friends and/or to the general public. As Facebook became more popular in the outside world, most users started feeling exposed as parents, bosses, teachers, employers and children all flocked to join Facebook.

Facebook has been transgressing privacy norms from the time of its inception and hence keeps finding itself in the middle of intense debates surrounding matters such as who owns the user’s information uploaded onto the site. Zuckerberg stated in his keynote announcing Open Graph that he wants to build a world where the default is social. But default settings are part of the reason Facebook is always in news. Facebook has made some serious social-networking infringements and has taken full advantage of people’s general apathy towards reading privacy rules and regulations. Whenever Facebook has updated its policies, it has set users’ privacy to the highest extent of exposure possible. The onus was then on the users to set it back to their preferred setting. If Facebook poses such a threat to their privacy, it would make sense that users would simply stop using it altogether, but clearly, that is not the case. The number of people joining Facebook hasn’t dwindled; the lack of privacy settings hasn’t deterred potential users. Statistics reveal that one out of every fourteen people in the world has a Facebook account. Despite the concern over lack of stringent privacy policies on Facebook, why are people reluctant to delete their accounts?

‘The mission of the company is to make the world more open and connected,’- Zuckerberg.

Facebook’s success lies in its skill of weaving itself into the fabric of modern life. Zuckerberg believes that most people want to share more about themselves and their lives online. ‘The way that people think about privacy is changing a bit,’ he says. ‘What people want isn't complete privacy. It isn't that they want secrecy. It's that they want control over what they share and what they don't.’ [v] Facebook has managed to deceive people into believing that one is in control. Over time people became comfortable exposing their vulnerable side to the public. Also, Facebook has become really good at making itself indispensable to its users. Losing Facebook hurts. People realised that the loss of being disconnected from such a large social platform is much more than their loss of privacy.

Another reason for not leaving Facebook would be the inability to do so. In other words there is a general perception that you can join Facebook but never leave. Facebook states – ‘in case you want to come back, we save your profile information (friends, photos, interests, etc.) so that your account will look just the way it did when you left [vi].’ Facebook lets you deactivate your account but not delete it. Off late, owing to the resistance and negative feedback from its users, Facebook has introduced an option to delete your profile once and for all. It won’t be surprising if only a handful of people are aware of this, as neither this news was circulated worldwide nor this seemingly easy to perform action is so easy after all.

With the introduction of social networking sites and monitoring devices, the social attitudes and values of this generation altered. Some say that the social norms of this age is something that has emerged out of the design of social networking sites, and some like Facebook’s Zuckerberg feel that the technology of social networking sites doesn’t control the social practices of its users. The definition of privacy provided by Zuckerberg is a very accurate hunch, as the world seems to be responding and agreeing with his ideology. Facebook has been very good at anticipating social behavioural changes rather than coercing people to open up and share private information. ‘Facebook has become a kind of virtual pacemaker, setting the rhythms of our online lives. Facebook did not invent social networking, but the company has fine-tuned it into a science.[vii]’

2.0. BACKGROUND OF THE TWO HOUSES

This chapter situates the reader within the context of the two glass houses. The Glass house was completed in 1949 and the Farnsworth house was completed in 1951.

2.1. GLASS HOUSES

The glass wall had its birth in the picture window during Le Corbusier’s period, post-war American architecture. In the first half of the 20th century, architects worked with the idea of getting the outside in or dissolving the boundary between the inside and the out. This dissolving of boundaries led to a different kind of domestic environment that redefined the meaning of habitation. The habitants faced the challenge of dealing with visual exposure of their living space. Use of glass in residential buildings invited the gaze in. The house had now become a theatre set.

Glass houses challenged the social values and norms of 20th century America. Had the norms of social structure changed? Or had the stage for the performance and exhibition changed?

2.2. THE IDEAL HOUSE AND THE FAMILY

‘The test of American civilization is not the height of its literary, musical, or artistic peaks, however important they are on the cultural landscape. It is the quality of the daily life itself... The greatness we search is greatness in the lives of our people. The true and the beautiful we try to combine with the good –and we call it the good life.’ Joseph A. Barry [viii].

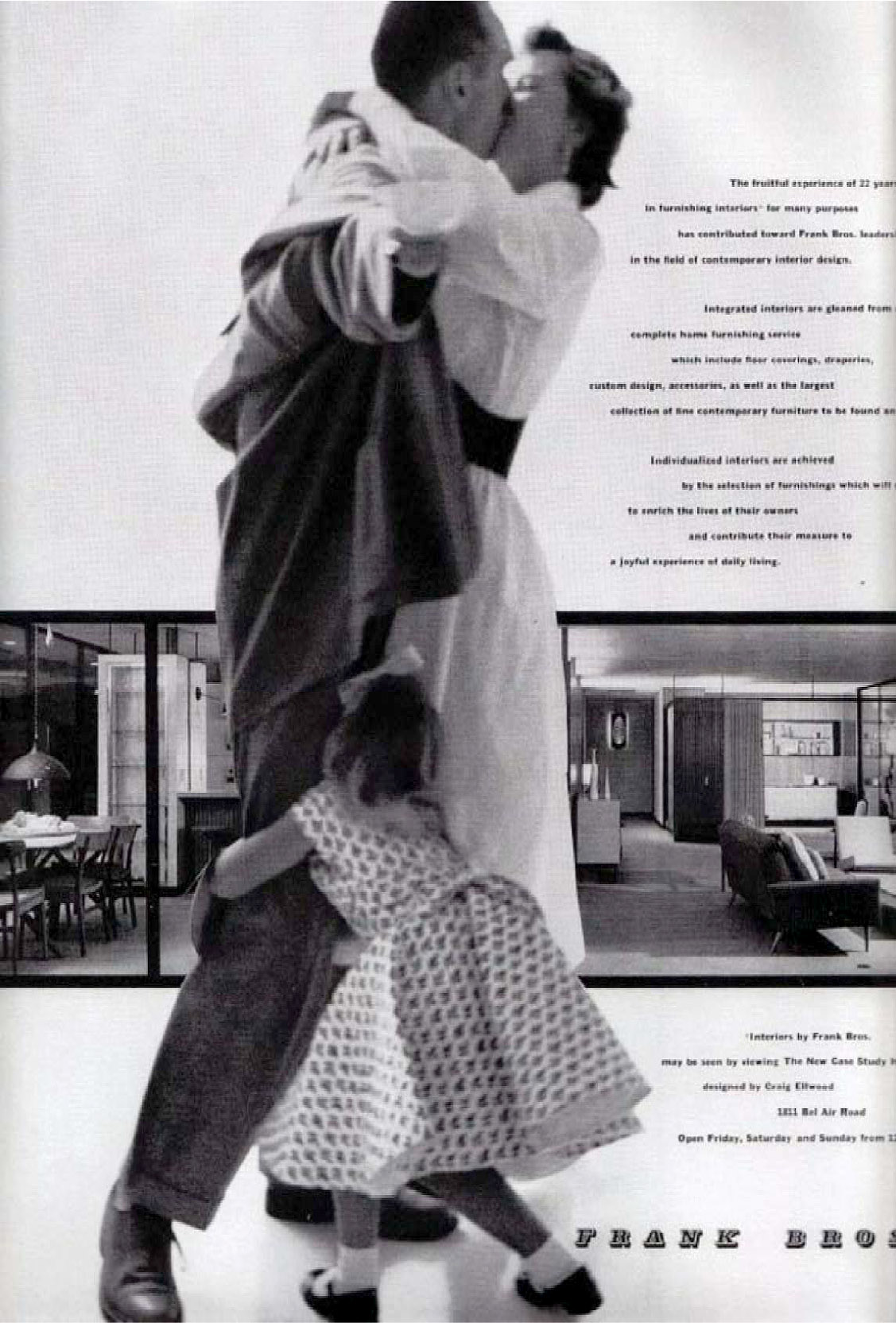

Advertisements, magazines and books of 1950’s America, advocated the happy family. Books like Benjamin Spock’s Common Sense Book of Baby Care and Child Care became extremely popular. Advertisements for houses in home magazines turned the American house into an equivalent of the orgone box. Marriage and family life were celebrated in these mediums. The word ‘family’ became synonymous with a home comprising of husband, wife and children. An ideal home always housed a happily married couple with children. The introduction of television though, blurred the distinction between the private and the public to some extent yet looked at women as homemakers. Motherhood was showcased as a full time profession for women. The house focused on an environment which was conducive for bringing up a child.

There was huge gap between the words ‘family life’ and ‘singleness.’ Social relationships outside the network of family (husband, wife and children) were not acceptable. Childless mothers were looked down upon and viewed with pity as people who missed out on the real pleasures of life. Single women and men were looked upon suspiciously and were considered mentally instable or homosexuals. The unmarried woman was seen as a ‘frustrated old maid’ who had ‘failed so seriously in her understanding of a woman’s role that she hadn’t even established the marriage prerequisite of having a home[ix]‘. Anne Parsons[x] mentions in her unpublished autobiography, ‘life for the unmarried person after twenty five or so is simply not very easy because by this fact one is thrown out of all the better-worn social grooves so that even relatively simple things as what to do on a Sunday become impossibly difficult.’ She also writes, ‘For mainstream America the single woman was like some sort of poison in the social system (that) has to be cast out’ and points out that she would be invited to the suburban houses for dinner only on rare occasions.

During the same time, the presence of women was being increasingly felt as more and more of them started having careers, stamping an authority professionally. Also, television had revolutionised the way society looked at women. Women started getting noticed. Anti-gay sentiments were also gaining force during the early 1950s[xi]. It was predominantly amongst the middle class or the bourgeois that this sentiment was being noticed in. Concern grew that the gender structure of their culture was being threatened. They considered homosexuality as muliebral behaviour by men, and career oriented or single women were considered to have masculine characteristics. This led to codes of appropriate social behaviour to be outlined giving birth to questions about privacy and surveillance. Post-war America had coined a new word-‘normal’- and outlined new norms of the importance of being and appearing ‘normal’.

3.0. COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE GLASS HOUSES AND FACEBOOK

3.1. SOCIAL STRUCTURE

Farnsworth House:

The Farnsworth house was built for a female client. The occupant of the Farnsworth house, Dr. Edith Farnsworth was an unmarried doctor who lived and worked in Chicago. When she decided to get the house built, she was in her mid forties and financially stable and secure. The weekend retreat would help her relax and relieve her from the stressful life she led as a doctor. She was painfully lonely and bored, according to her memoirs, and this weekend getaway would help her escape the lonely weekends she spent in the city. A house for a single, professional woman defied the popular home ideas and ownerships for married couples and challenged social acceptance. Ms. Farnsworth may have been a very successful doctor, but the fact that she was unmarried deemed her unsuccessful in the eyes of the society.

Mies wanted the space to be left the way he designed it. He had envisioned the space to be without children, pets, or any other human being other than Ms. Farnsworth. The architect was so insistent on keeping his composition of the space sacred that he preferred not even additional furniture be added to the house, other than the ones suggested by himself. In this regard, Mies had found the perfect client in Ms. Fansworth. She was single, and he may, through his acquaintance with her, realised that she didn’t plan to ever have a companion or children, though the lack of a companion being a consequence of the environment she had to live in, is very much possible. Ms. Farnsworth seemed to have been misled by the drawings and models of her house presented to her by Mies. She had played an active part in designing her house, and was in unison with him throughout the design phase. The model showed the walls to be opaque. One Sunday, during their visit to the site, when she enquired about the material used to construct the house, Mies replied, ‘I would think here where everything is beautiful, and privacy is no issue, it would be a pity to erect an opaque wall between the outside and the inside. So I think we should build the house of steel and glass; in that way we’ll let the outside in. If we were building in the city or in the suburbs, on the other hand, I would make it opaque from outside and bring in the light through a garden-courtyard in the middle.’ In his quest to define modernism he exhibited Ms. Farnsworth’s single life to the world.

Glass House:

The client and the occupant of the Glass house was the architect Philip Johnson himself. Johnson lived in this house for about 50 years. The house was autobiographical and presented the alternate (with respect to 1950’s America) mode of living - the life of a gay man. 1950s’ American society did not approve of homosexuals, looking at the glass house with the same loathing air as the Farnsworth house.

3.2. CONTEXTUAL INTEGRITY

This paper applies Professor Helen Nissenbaum’s theory of privacy as contextual integrity[xii] to analyse problems regarding privacy. In order to understand issues about privacy, it is important to understand the environment inhabited by an individual. Privacy is constituted by the reciprocal relationship between an individual and the environment. The informational properties of Facebook’s environment are different from the physical world, yet the contextual integrity and the networking within any environment are co-related.

The practice of privacy is a result of dynamics within the environment. As the social psychologist Irwin Altman explained in The Environment and Social Behaviour[xiii]: ‘Environment and behaviour are closely intertwined, almost to the point of being inseparable. Their inseparability says more than the traditional dictum that ‘environment affects behaviour.’ It also states that behaviour cannot be understood independent of its intrinsic relationship to the environment and that the very definition of behaviour must be within an environmental context. ‘What is now called for (is) recognition that the appropriate unit of study is a people-environment unit.’ Here, ‘environment’[xiv] means the properties and structure of a space, specifically those that affect user decisions, practices, and risk assessments within it, i.e., the architecture[xv] of the space. The architecture of a space affects human behaviour in the same way the design of a digital space affects human behaviour within that space.

Facebook :

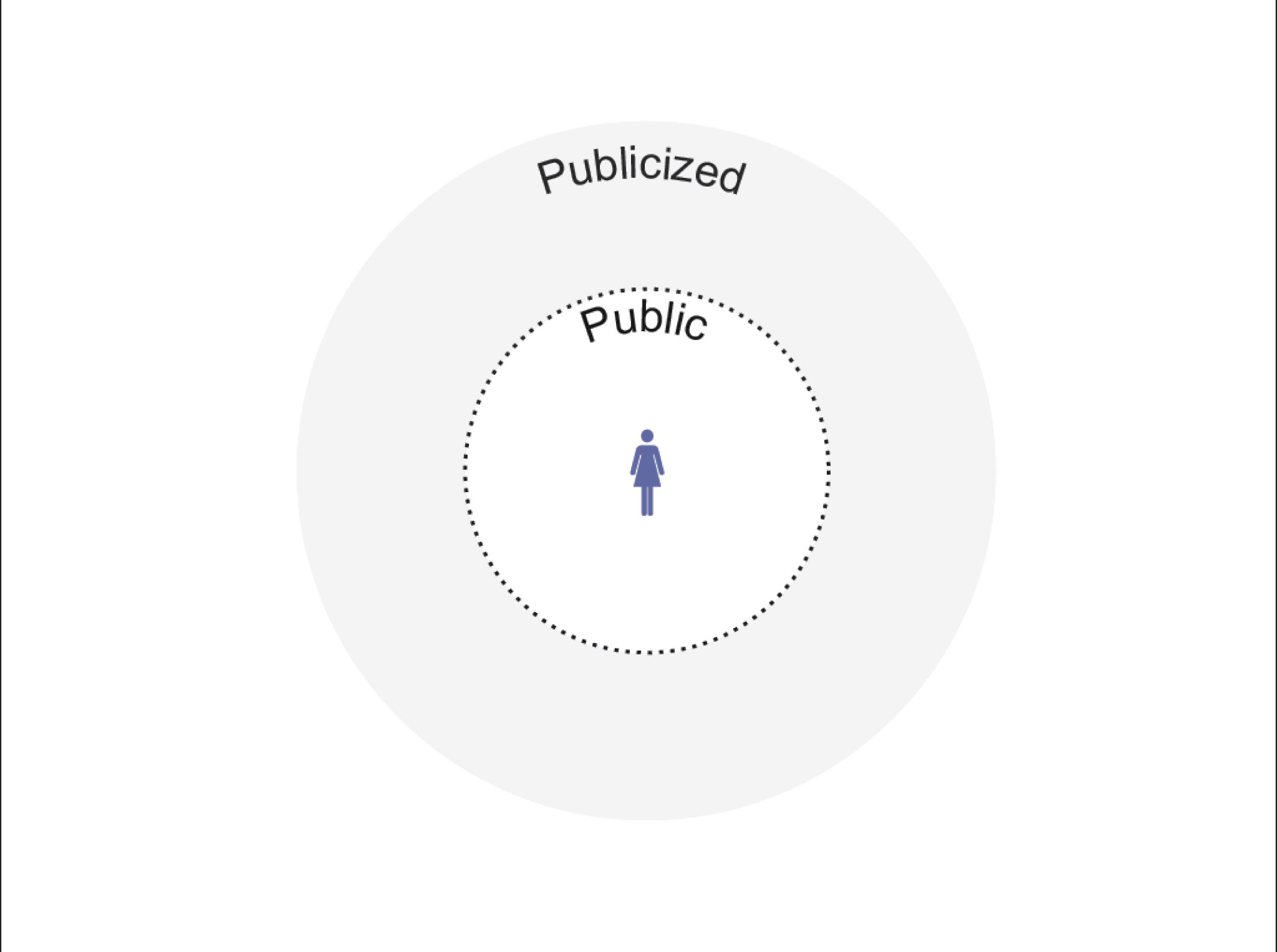

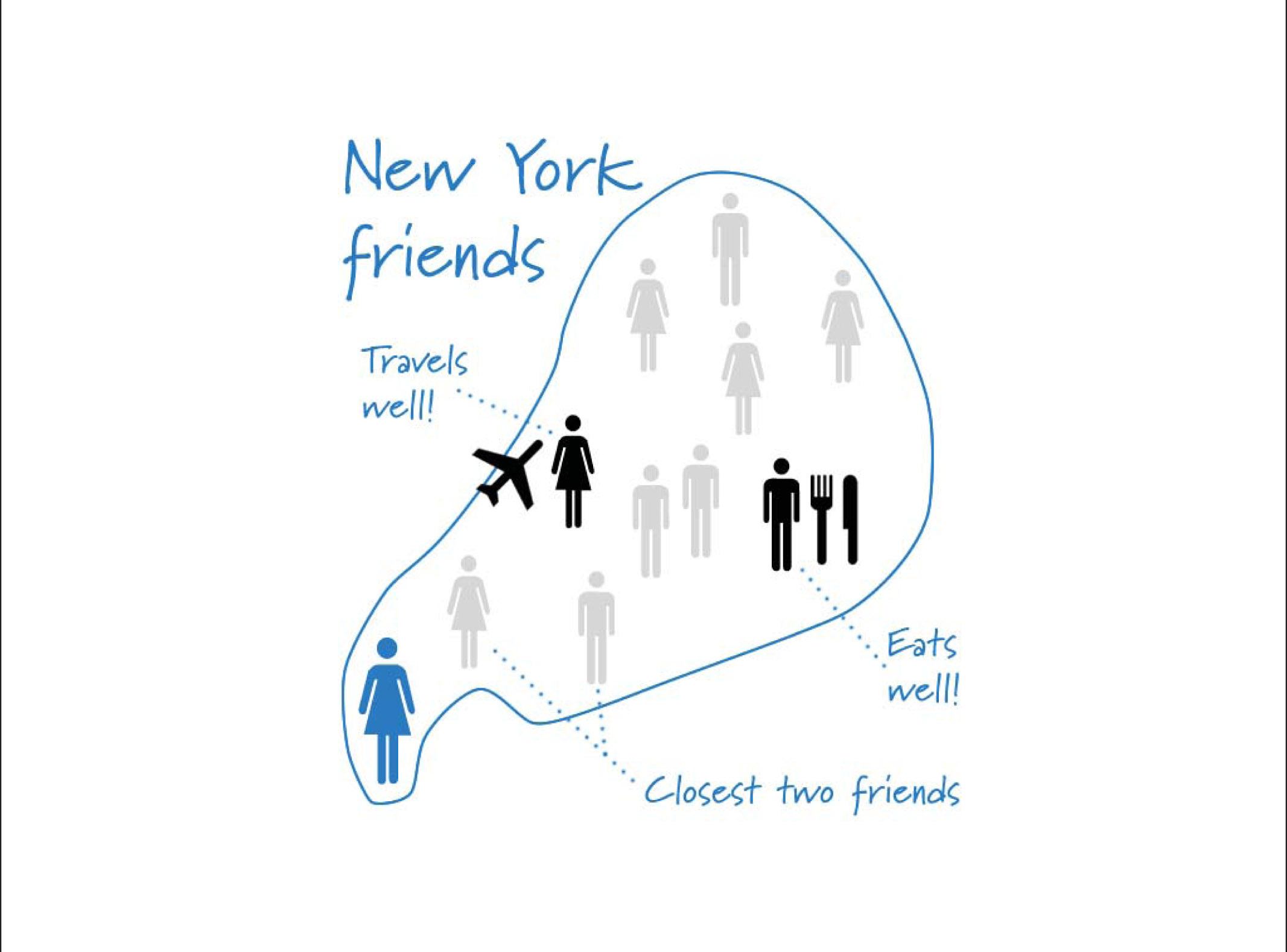

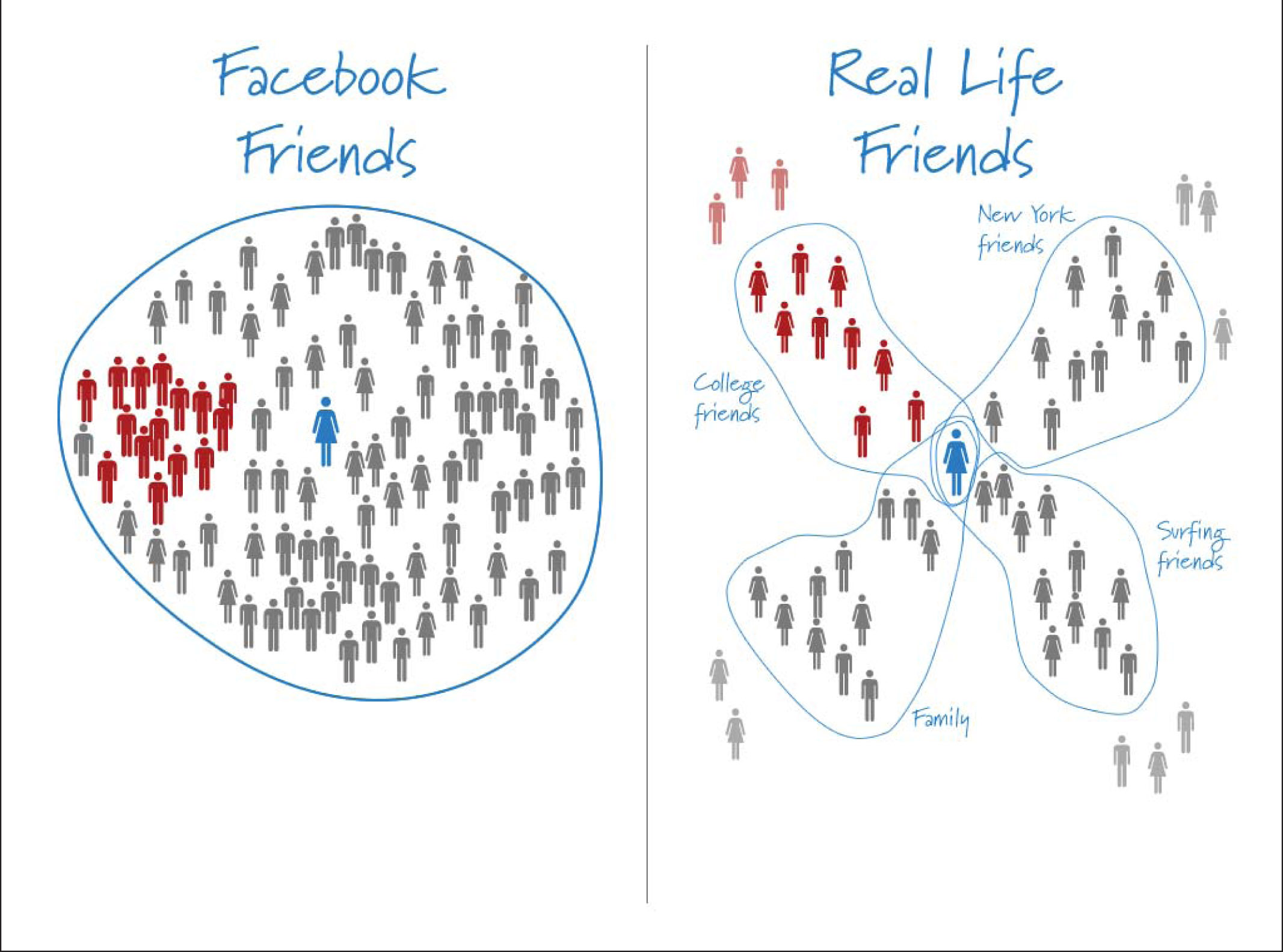

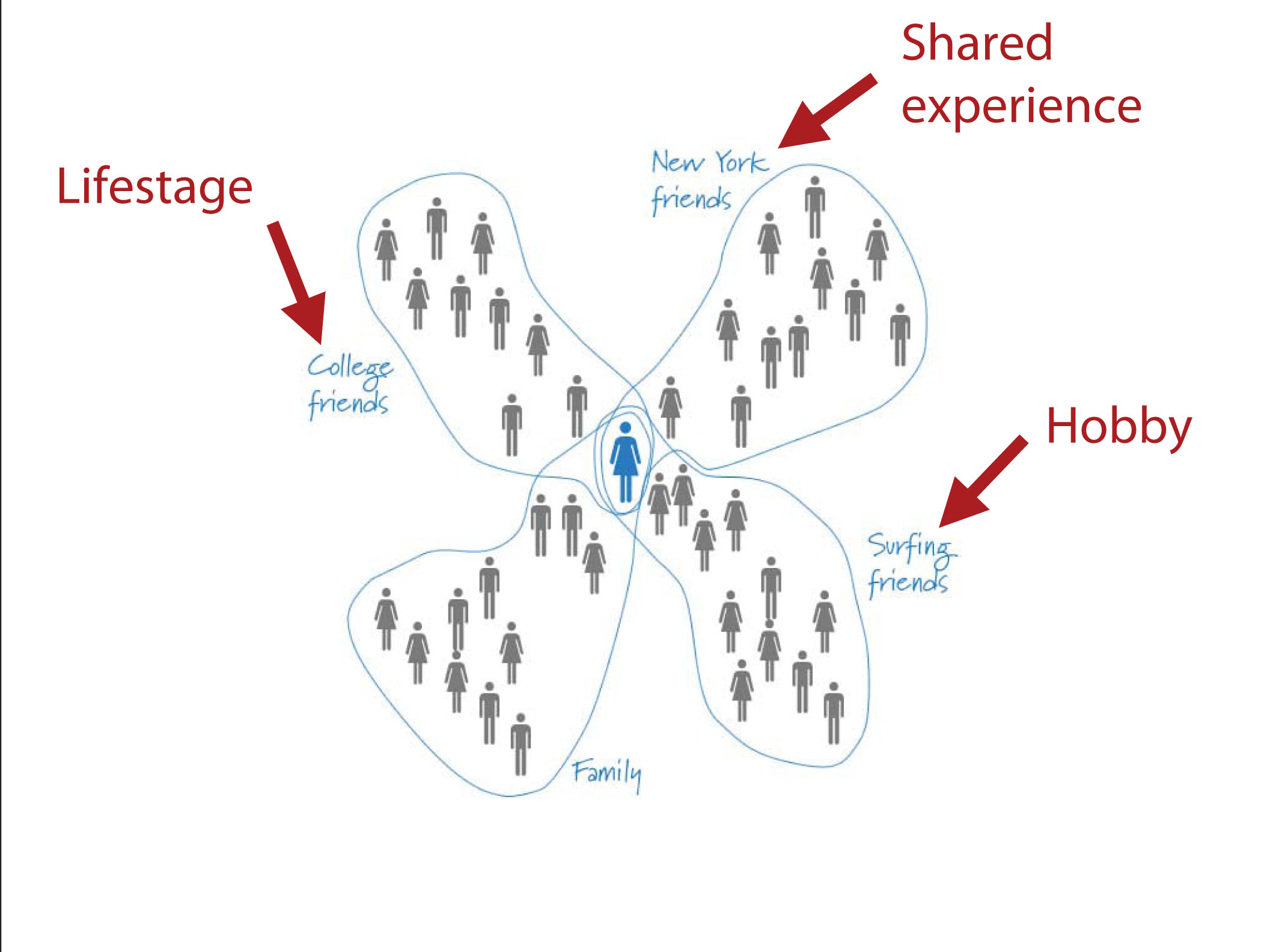

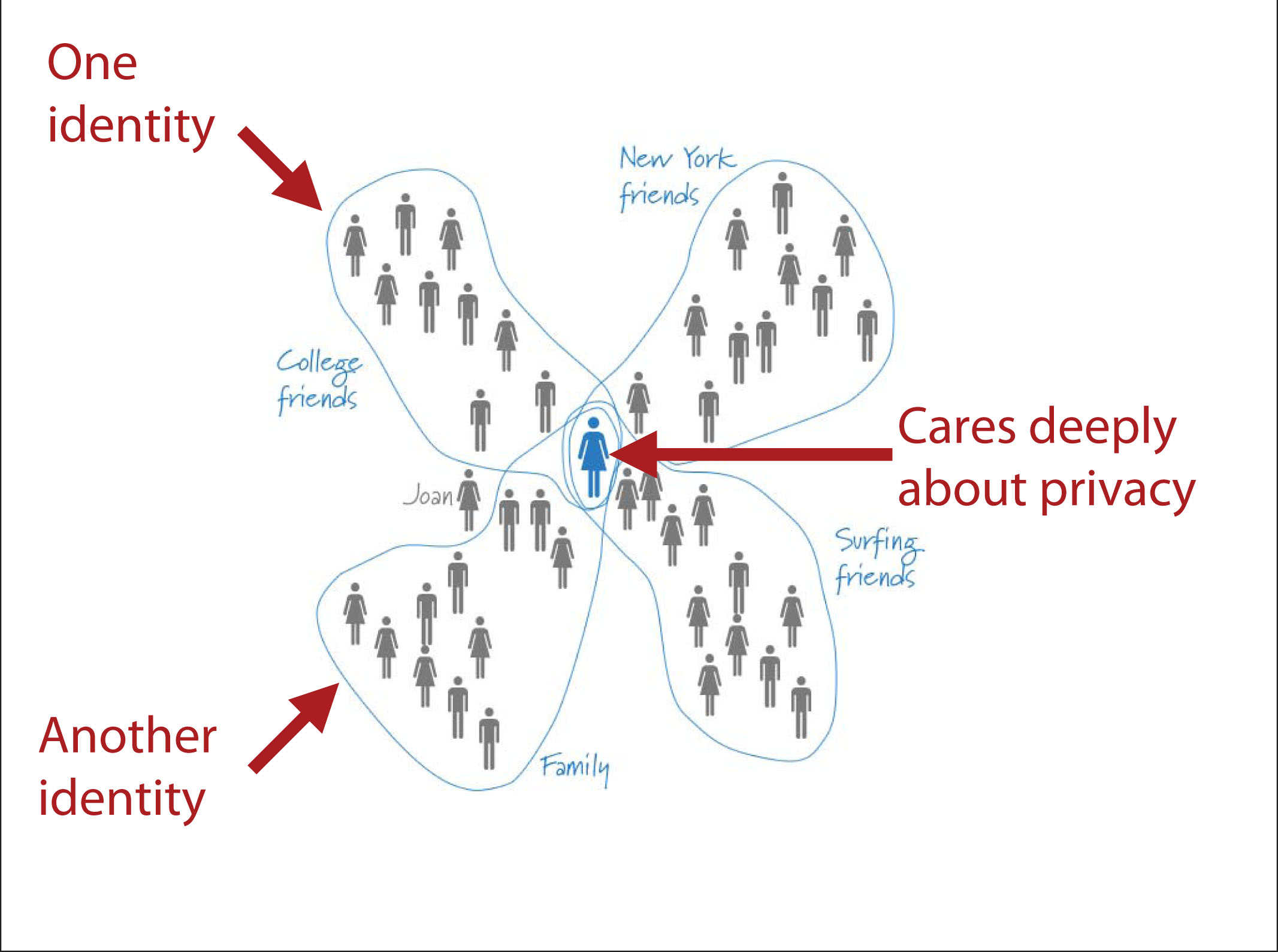

Privacy allows one to maintain varying degrees of intimacy, basically variety of social relationships. Privacy entitles us the power to control what information people get about us and who gets it and thereby allows us to vary our behaviour with different people and maintain the various social relationships. In other words, it maintains the social integrity of the relationships. Usually everyone plays a different character within different social contexts. However, Facebook disregards any categorization of social situations or social groups and hence it becomes difficult for users to know who is watching. Facebook’s concept of friend is anyone one adds[xvi]. Hence, in an environment like Facebook, there is no distinction between social contexts leading to a collapse of the different worlds. This breakdown is what the theorist Helen Nissenbaum calls loss of contextual integrity[xvii]. Nissembaum argues that privacy is violated when individuals do not respect social norms of appropriateness and distribution. By appropriateness he means, what data may be shared in a given situation and by distribution he means, how and with whom data may be shared.

Different cultures or generations have different social norms of appropriateness and distribution. A major flaw of social networking sites is that it doesn’t allow segregation of audiences. It collapses complex social relationships; the different cultures and generations into one platform-the interface of the Facebook profile. It’s the design of social networking sites that contributes to this breakdown of social integrity.

Facebook does offer segregation of audiences through privacy functions on the page and by establishing groups. The degree to what one can actively exclude individuals is very questionable but as mentioned earlier the notion of having control seems to be working though it has been periodically met with resistance. But one should note that the introduction of the privacy filters has been strategically timed when people have accepted and got comfortable with the default privacy settings. The default privacy settings of Facebook were that the profile is visible to everyone. Though a person can create extremely effective privacy filters by categorising the friends (Facebook’s definition of friend) into its desired categories, it is impossible to emulate the nuances of social structures of the physical world. Filtration in the physical world can’t be the same as the visual world but it is slowly inching towards equilibrium. The nature of relationship in the visual world is influencing how people behave in the physical world too.

Farnsworth house and Glass House:

Mies’ ideas concerning the exterior would have worked perfectly fine had it not been for the interior and the fame the house received. There were other factors too which contributed to the failure of the functionality of the house with respect to Ms. Farnsworth’s experience, during her stay in it. Mies had envisioned the site to be uninhabited open landscape and hence the issue of privacy and the outside gaze was not considered.

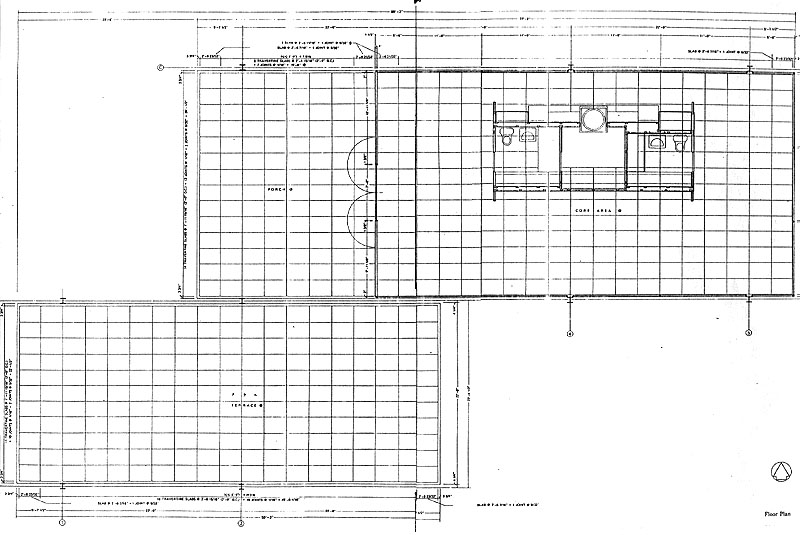

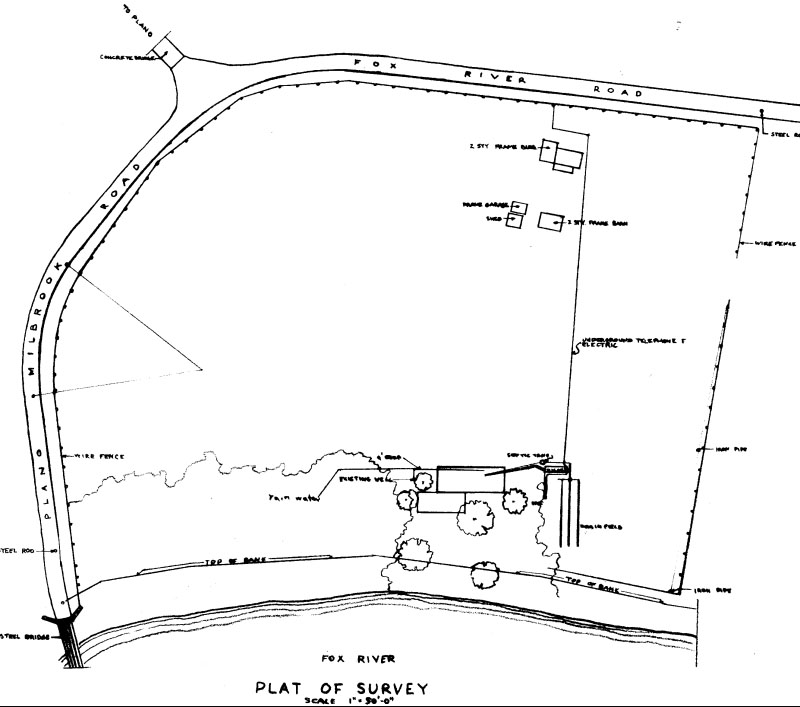

The house is located 55 miles southwest of down-town Chicago on a 60-acre estate site. It is situated in the middle of a grassy meadow and adjoining it runs the River Fox, south of Plano, Illinois. Here, the context becomes extremely important as unlike any office building situated in a commercial area, the house was not placed in an environment where it was vulnerable to the public view. The privacy needs of these two programs definitely differed, the Farnsworth house being a residential program and an office building being a commercial one. Yet, if a glass house (residential program) was to be placed in a context where the distance between two adjacent properties was extremely minimal and the social structure of the probable audience were different than its present context, privacy issues would have been different. The only way a glass house would work in the present context is if the distance between two adjacent properties is generally much more than in the city and also if the probable audience would be the residents of the houses nearby, thereby reducing privacy issues.

The Glass house was located in New Canaan, Connecticut within his own estate that housed other structures designed by the architect Johnson himself. It is located behind a stone wall at the edge of a crest in the estate overlooking a pond. Johnson had designed the surroundings in such a manner that the house was hidden from public view. The fact that the Glass house was built in his own estate allowed the architect to control the surroundings and design it according to his own desires, letting it remain unaltered for as long as he pleased or lived. Mies had merely placed the box in the surrounding; he did not design the immediate surroundings of the house. Hence, in the case of the Farnsworth house, the client did not have control over her surroundings. In 1968, the local highway department claimed a 2-acre portion of the property adjoining the house for a new, raised highway bridge over the River Fox. Farnsworth sued to stop the project but lost the court case. Ms. Farnsworth, though, faced plenty hardships during her stay in the house lived in the house for 20 years and sold the house in 1972, only after losing the court case, realising that the placement of the house beside a highway would have led to the complete breakdown of contextual integrity.

3.3. A MATTER OF IDENTITY

Identity is very closely related to image. Identity is what we are; it is defined as the state of being oneself or itself, whereas image is how one is viewed by people, which is undeniably influenced by how one projects themselves in front of people. Identity can’t be constructed but is constitutional whereas an image can be constructed. The construction of a person’s image takes place in a closet. The memory of oneself is usually made up of the image that one saw of himself /herself in the mirror in his closet.

The word ‘closet’ has two different meanings one as a place for storage and the other as a metaphor for the identity of a person. The term ‘being in the closet’ refers to a person concealing his homosexual identity from the public, and hence the gay rights movement’s war cry -‘out of the closets, onto the streets’. The former usage of the word closet refers to a room which is meant to house clothes, placed within a room meant to house people, essentially making it a room within a room. The smaller room - the closet- houses things that might disturb the organization of the bigger room where a person lives if kept there. In a way, the smaller room conceals contents from the public eye. The usage of the word ‘closet’ in the latter case signifies that the person is reluctant to publically claim his sexual identity. Both these meanings deal with storage or secrecy and display or disclosure, in their respective contexts.

For centuries, people have stored their clothes in cupboards or hung them by hangers inside them. The built-in closet is a relatively new variation of the earlier days’ cupboard, yet all these perform the primary function of storing and concealing clothes from the public eye. During the 1840s’, the closet itself was looked at as a shameful secret and was kept hidden from the view of anyone entering the space in which it was kept. During the 19th and the 20th century, too, the smaller room was kept away from the world. Only family members or close friends had the privilege to view the contents of an individual’s closet, almost always with the consent of the owner. No one is comfortable displaying the contents of their cupboard or closet to the public. It’s almost like revealing themselves naked. Hence, the closet was and is always placed in such a way that it is inconspicuous within the room. Its designing and basic architecture has always remained the same. In other words, its function to conceal its contents hasn’t changed.

Here, the ‘closet’ is about individuality. Though the contents in the closet are revealed to the public whenever the owner adorns them, rules of social context are followed. The choice of what is revealed to whom is connected to the varying degrees of intimacy. The closet helps an individual to follow and abide to the rules of contextual integrity. If we could imagine the closet being made up of glass, it would be a clear loss of contextual integrity.

Farnsworth house and Glass House:

The plan shows the existence of two bathrooms and some space between in the Farnsworth house. Mies had provided bathrooms anticipating guests in the Fansworth house and he wanted to separate the only private, intimate space in the house - the bathroom from the visitors. According to Alice Friedman, the provision of two bathrooms suggested a desire to hide the modesty of the female body. The guest bathroom was meant to keep visitors from seeing ‘Edith’s nightgown; the emblem of femaleness, sexuality and the body, on the back of the bathroom door[xviii].’ This also reveals Mies’ attitude, which was also the attitude of 1950s American society towards single women; that they had very little of their private lives to conceal and that only the nightgown, the sign of her body, was worth concealing.

Every person has a certain aspect of their lives that he wants to keep private and certain aspects that they are comfortable displaying to the public. The fact that Philip Johnbsp;nson was gay was known to his circle of friends, students and critics. But like other gay men of that era, (before gay liberation) he was forced to wear a mask when he was out in public. The glass house signified the overt side of domestic life and the guest house signified the hidden side of it. The guest house played the role of a closet here.

Though the interiors of both glass houses were exposed to the world, making it vulnerable to the world’s eyes, the physical and the social context of the surroundings did anticipate only a particular category of audience. As seen in the case of the Fa style= rnsworth house, due to the development of its surrounding areas and the transformation of the house from a weekend retreat to an exhibit, owing to its fame, the architect was not able to restrict the audience to its anticipated category. This led to a loss of social integrity.

In both cases, the architect hid the closet and in a way hid his client’s identity. The walls, doors and furniture of the house might betray the owner’s identity but the closet would never. The closet in both the houses safeguarded their owners’ secret - the absence of a marriage gown or marriage bands.

3.4. INVISIBLE AUDIENCE

Facebook:

The way we behave and what we say often depend on the audience. People modulate their tone and volume of their voice during conversations depending on the sensitivity of the content and who is within earshot. People wear appropriate attire to any place considering social norms of the space and the situation. In the physical world, it is possible to comprehend social and architectural dynamics of the space and detect the audience, but in the electronic media it is not possible to do so. Danah Boyd has characterized this as a problem of ‘invisible audiences,’ noting that since ‘not all audiences are visible when a person is contributing online, nor are they necessarily co-present it can be extremely difficult to fulfil normative expectations of social roles’[xix]. Invisible audiences deceive performers as they do not allow situational awareness. Boyd describes ‘the inability to perceive audiences on Facebook prevents users from realizing their misrepresentations.’

The window of Facebook works both ways; just as the audience is invisible, so too is the performer. Users on Facebook have an option of shielding their identity from the prying eyes of parents, professors, police officers, and other guardian figures. Profiles on Facebook become the image of a person. The image can be constructed and hence a Facebook profile allows for role play. Therefore, people, hesitant to give out their real identities, either adopt a pseudo one or reveal less. On Facebook, (as also other social networking sites) people can hide behind a screen - the computer - and keep their identity hidden. Facebook’s recently added privacy filters gave the users an option to introduce categories and create privacy filters, facilitating profiles being controlled impressions for specific audiences.

3.5. EXHIBITIONIST VS. CELEBRITY

Columnist Robert Samuelson, writing in the Washington Post, condemned social network sites as nothing but homes for ‘attention whores.’ ‘Exhibitionism is now a big business,’ He continued: What's interesting culturally and politically is that (the popularity of Facebook) contradicts the belief that people fear the Internet will violate their right to privacy. In reality, millions of people are gleefully discarding or compromising their right to privacy. People seem to crave popularity or celebrity status more than they fear the loss of privacy[xx].

Exhibitionists and celebrities have one thing in common: their personal information is exposed to the public. Exhibitionists are not embarrassed nor do they feel alarmed when their personal information is shown to others. Celebrities and politicians live a better part of their lives in a fish bowl; their privacy being threatened constantly. But they might have a sense of revulsion when their personal information is made public. On Facebook, personal information is shown to others by default. Does that classify all users as either exhibitionists or celebrities?

Danah Boyd mentions, digital natives are the first generation to grow up living in celebrity-style publics[xxi]. Invisible audiences have the potential to turn anyone into a celebrity, because they watch with unseen eyes, obscure norms of appropriateness, and lead to collision of contexts.

A lot of people had labelled Johnson as an exhibitionist. Johnson himself perversely boasted of the pleasure he derived precisely from the risk of exposure within the Glass House: ‘I mean the idea of a glass house, where somebody just might be looking—naturally, you don’t want them to be looking. But what about it? That little edge of danger in being caught. Sometimes a little kid masturbates because he wants to get caught[xxii].’ Johnson was an extremely influential and well known figure during his time. Apart from his circle of friends, architects, architecture students, art circle he was known in the media and press too. A lot of the popularity he received was owing to his own efforts in marketing himself. He craved for attention, unlike Ms. Farnsworth. The Glass House became a stage upon which Johnson performed and controlled the performance of his public life and the brick house shielded his private life from the public. Johnson enjoyed the ‘edge of danger’ and the risk of exposure precisely because he created both means to control and escape the gaze.

3.6. THE GAZE

The window is a mediator between spaces and it also holds true in the case of electronic media. In the case of the glass wall, the window is no longer a puncture in the wall, but the wall itself. The function of a wall is to provide privacy (besides shelter and protection from nature) by blocking an outsider’s view of the inside of the house. The problem arises when this function of the wall is altered. Society, familiar with the earlier properties of the wall, finds it extremely hard to adjust to its new functionality. The glass wall exposes the vulnerability of its occupant to the prying eyes of the viewers. This wall is a place of the visual and a place of visual display. The glass window frames views to the outside when viewed from inside, but it also frames views to the interior of the house when viewed from outside. It turns the house into a theatre set upon which the daily life of the occupant is performed or enacted. The glass house didn’t represent domesticity, and it was incapable to function as a family house in the 20th century.

‘I can feel myself under the gaze of someone whose eyes I do not even see, not even discern. All that is necessary is for something to signify to me that there may be others there. The window if it gets a bit dark and if I have reason for thinking that there is someone behind it, is straightway a gaze. From the moment this gaze exits, I am already something other, in that feel myself becoming an object for the gaze of others. But in this position, which is a reciprocal one, others also know that I am an object who knows himself to be seen.’- Jacques Lacan [xxiii].

Interestingly, the excitement of viewing is derived from a voyeuristic indulgence. Dorothy Kalins writes in her essay ‘the essential thing is that he must believe that if she knew she was being observed she would immediately pull the shades. She must never know that the concept of privacy has been broken. Once she acknowledges that, he loses his pleasure of watching.’ During the day time due to the glare caused by the rays of the sun, the interiors of glass houses aren’t exposed to a great extent but after dark, the habitants are faced with the problem of being seen without being able to see.

One more interesting thing about looking is that if caught, people wouldn’t mind being caught looking at something rather than someone. This becomes extremely relevant in the case of elevators and subway trains. Staring at anything other than meeting co-passengers gaze is considered correct social behaviour. Here, the distance between the observer and the observed becomes very important. Dorothy Kalins writes about the high-rise, curtain walled office buildings which changed the space inside and the whole concept of privacy. Any two adjacent glass office buildings had access to each other’s interiors. But since the interiors of office spaces do not have much variety and looked similar to each other, it is almost like looking at a mirror image than looking inside a window. Hence, people didn’t stare at others working in these office buildings. Also, the office building being a public place in itself, people were aware of the fact that they were exposed to the view of the others present in the room and an addition of a few more pairs of viewing eyes did not affect them as much.

Farnsworth house:

Sometimes it is not necessary that the observer is present outside the house. The mere thought that others can see us from any particular point makes us feel exposed. Mies failed to create a house that made its inhabitant feel protected. In an interview with House Beautiful in 1953 Farnsworth complained, ‘In this glass house with its four walls of glass I feel like a prowling animal, always on the alert. I am always restless [xxiv].’ Ms. Farnsworth felt helplessly exposed. She wrote that she found it ‘hard to bear the insolence and boorishness of those who invaded the solitude of (her) shore and (her) home.... flowers brought to heal the scars of the building were crushed by those boots beneath the noses pressed against the glass.’ Even though she did not meet the trespassers, the crushed flowers provided evidence of their presence.

In the case of the intruders, the consolation that their object of observation is the house and not Ms. Farnsworth herself relieved them of their guilt. They didn’t consider it offensive to intrude her privacy as the house had become an exhibit and as mentioned earlier, they considered it as observing something rather than someone.

‘Do I feel implacable calm?’ she repeated. ‘Even in the evening I feel like a sentinel on guard day and night. I can rarely sit out and relax...What else? I don’t keep a garbage can under my sink. Do you know why? Because you can see the whole kitchen from the road on the way in here and the can would spoil the appearance of the whole house. So I hide it in the clothes hanger in my house. Any arrangement of the furniture becomes a major problem, because the house is transparent, like an x-ray.’

The Farnsworth house was extremely minimalistic and the interior lacked any drama or character other than a Miesian minimalistic interior showcasing ordered geometry. The positioning of the furniture had a lot to do with how Ms. Farnsworth felt. The furniture always drew the inhabitants gaze to the outside, reminding them that the wall is made of glass and people from outside can see you. Though the service core in the centre was the focal point of the house, yet it lacked drama. The vision or the focus of the inhabitant was always directed outwards. The house had started dictating how she would inhabit the space. The house started controlling her.

Glass house:

In spite of Johnson publically expressing his debt to Mies and mentioning that the Glass house is a derivative from the Farnsworth house, these two houses have a lot of differences. The most remarkable difference being that the transparent Glass house was paired with the opaque Guest house. Johnson in a way tricked his audience - though he maintains the glass house was never meant to be in isolation - yet he deliberately focussed on the Glass house and people conveniently forgot all about the Guest house. Plenty of criticisms and articles written about him and the glass house negate the existence of the brick Guest house. The glass house was about the outside whereas the Guest house was about the inside. The Guest house housed the private life of Johnson whereas the Glass house showcased his public life.

The arrangement of furniture in the glass house allowed for daily chores to take place without being reminded of the outside gaze. Johnson had positioned the furniture within the interior in a way that it created spaces within a space. He mentions in the book Glass house ‘so it’s a set of enclosed things’. The image 17 shows lights reflecting and creating a glow on the brick ceiling against the brick wall as also the glow of the fire place. Strategic placement of furniture and lights within the house lent a dramatic and sensuous character to it, unlike Mies’ ordered geometry. The drama within the house kept the inhabitant’s gaze directed towards the interior, and unlike the Farnsworth house did not remind them of the transparency of the glass walls.

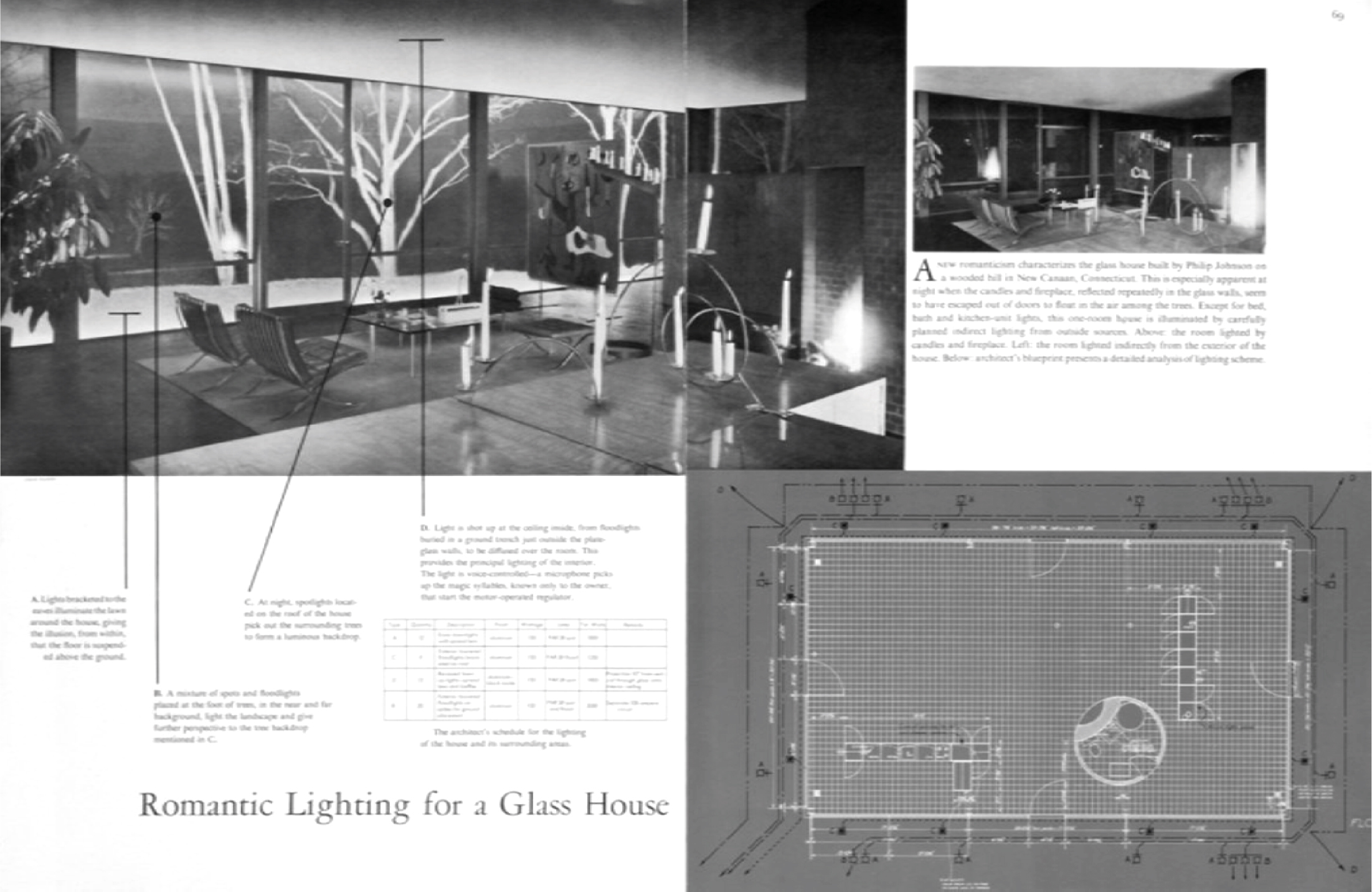

The design of the glass house was not restricted to the glazed walls alone; Johnson had carefully designed the exterior landscape in contrast to Mies whose approach was an intervention within an uninhabited landscape. The interior layout and the surrounding landscape screened and denied visual access to the inside of the house. Provision was made to light the exterior of the house during night. The lights illuminated the lawn and the trees surrounding the house, exposing the outside to the inhabitants inside the house, when the house itself is extremely vulnerable to the intruder’s gaze. Hence, in the Glass house the observer outside it was exposed to the inhabitants of the house at night unlike the Farnsworth house. For Johnson, the design of the Glass house was as much the exterior as the interior.

EPILOGUE

The Farnsworth house and the Glass house challenged the values of 1950s’ America. The conventions of domestic planning during this period were closely related to heterosexual norms of living. These two houses questioned the contested values of gender and sexuality. It raised questions about residential building typologies as patterns of domestic life. In a way, it revolutionized the way people lived. It made people realise that a family was not the only type of client a residential house housed. The lives of an unmarried individual and/or homosexuals that were shunned during this age were suddenly in focus. These houses were instrumental in bringing about a change in the outlook of American society towards singles and homosexuals.

The Farnsworth house was designed for the occupant, the Glass house for the occupant as well as the viewer whereas Facebook was designed for the viewer initially and later transformed when met with resistance from the occupant. In this age of monitoring and surveillance, one thing that a person has control over is their true identity. Digital footprints are left everywhere on a daily basis - in hospitals, banks, airports, offices, supermarkets etc. An image is created everywhere, whether constructed or revealed. Everywhere there’s a performance going on, there are eyes watching it and people are getting comfortable being watched. The concept of identity related to the closet mentioned earlier becomes relevant in this age, where people are habituated to living in celebrity-style publics. On Facebook, though people reveal their personal information to the public, they still hide behind a screen. People are not scared of exposing their vulnerable side to invisible audiences online, but, in the real world people are still hesitant. The last century has seen a rise in the use of glass in architecture as also in residential projects. More and more people are becoming comfortable living in glass houses. If not completely true, the trend surely shows that we are heading towards an age of transparency. The closet still gives us an option to safeguard our identity from the public and keep it under wraps. The age of privacy might not be over, but the definition and concepts of privacy have definitely evolved. The entire world is tending towards one big stage.

In today’s society, the boundary between private and public is becoming more and more blurred. This blurring of boundaries was instigated by the glass house and revolutionized by Facebook. Boundaries give an identity to all kinds of systems. Boundaries give us a sense of belonging and ownership. The ability to have control over one’s personal information is important here. Boundaries are essential to maintain integrity. Facebook does grant the world a front-row seat to all of our interests, yet it does offer you the choice to draw the curtains. The Farnsworth house didn’t come with the curtains, the curtains had to be installed, whereas the glass house didn’t need the curtains.

[i] We here refers to Facebook users

[ii] Modernist period- late 19th and early 20th century

[iv] Dr. Ian Graham, “Putting Privacy in Context -- An overview of the Concept of Privacy and of Current Technologies” accessed July 20, 2010 http://www.iangraham.org/talks/privacy/privacy.html

[v] Dan Fletcher “How Facebook Is Redefining Privacy” , Time newspaper, Section Businness and Tech, Thursday, May 20, 2010 accessed July 25, 2010 http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,1990798,00.html

[viii] Joseph A. Barry,” The Next American will be the Age of Great Architecture”, House Beautiful, April 1953.

[ix] Alice Friedman. People who live in Glass Houses: Edith Farnsworth, Ludwig Mies Van Der Rohe, and Philip Johnson. In: Women and the Making of the Modern House. 1998 pp 126-159.

[x] The unmarried daughter of Harvard socialist Talco

[xi] According to George Chaucney, professor of history at Yale University.

[xii] Helen Nissenbaum, Privacy in context: technology, policy, and the integrity of social life ,2010

Jeffrey Rosen, the unwanted gaze: the destruction of privacy in America, 2000 (for a general application of the theory of contextual integrity to the Internet).

[xiii] Irwin Altman, “The environment and social behaviour” 205, Wadsworth Publishing Company, 1975. Originally cited in Zeynep Tufekci, Can You See Me Now? Audience and Disclosure Regulation in Online Social Network Sites, bulletin of science, technology & society,Vol. 28, No. 1, 2008, p. 20-36.

[xv] Thaler and Sunstein’s metaphor for the ‘organization’ of the context in which people make decisions.

Richard thaler & cass sunstein, nudge: improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness 8, Yale University Press, 2008 (definition of a ‘choice architect’).

[xvi] In the context of facebook it means accepting someone as a friend.

[xvii] Helen Nissenbaum, Privacy as Contextual Integrity : Technology, Policy, and the Integrity of Social Life” Stanford University Press, 2010

[xviii] As reported by Myron goldsmith in conversation with Alice Friedman, April 1988.

[xix] Danah Boyd, Taken Out Of Context: American Teen Sociality In Networked Publics (Fall 2008) (unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, University of California-Berkeley, School of Information), http://www.danah.org/papers/TakenOutOfContext.pdf., at 34. See also Grimmelmann, Saving Facebook, supra note __, at 1162, where he identifies the social heuristics of ‘Nobody in here but us chickens’ and ‘I think we’re alone now.’

[xxi] Danah Boyd, My Friends, mySpace. See e.g. Lamebook, http://lamebook.com (the functional equivalent of a shaming tabloid for Facebookers).

[xxii] Lewis, Hilary and O’Conner, John “Philip Johnson: The Architect in his own Words”. New York, Rizzoli.1994

[xxiii] The seminar of Jacques Lacan. Book 1. Freud’s papers on Technique, 1953-1954.

[xxiv] Wagner, George “The lair of the bachelor” In Architecture and feminism edited by Debra Colman, Elizabeth Danze and Carol Henderson. Princeton Architectural Press, 1996, pp.183-222.

/ /div Danah

pleft_edn5#_ednref9edn13

rsquo;s a set of enclosed things

Društvo

Društvo Društvo

Društvo